Just a week ago, I was blessed to spend New Years in Japan for the second time. The first was just last year while I was on vacation. But I had so many places to see, so the holiday season was a bit rushed. But this year marked my first time actually residing in Japan, so I got to experience all the interesting Japanese New Year traditions.

What’s the deal with New Years?

If I was comparing the event to New Years in America, I would say they’re drastically different. Apart from those who religiously watch the annual Times Square Ball Drop in-person or live-streamed on TV, there are no real New Years traditions. Sure, people throw parties, write New Year resolutions, play with fireworks, and dream of their midnight kiss…but there’s no contest as to which country does it bigger.

New Years is the biggest holiday of them all in Japan. Most work or businesses are closed for a few days to a whole week (usually the Dec. 31-Jan. 3) to focus on family. Children who’ve grown to adults and moved far away will drive or take the train back for a year’s end homecoming. Here’s what a typical Japanese New Year is like.

Before making the trip

End-of-year-cleaning

In America or other Western countries, you might have heard the term “Spring cleaning”, where we clear out old things in the beginning of that season. But in Japan, they have an event called o’souji (お掃除, lit. cleaning), which happens at the end of the year instead.

Typically, the year’s end amasses a collection of dirt and dust in places you don’t usually pay attention to when cleaning. So now is the time to get dusting and scrubbing, airing out the futon and tossing away old things.

Typically, the year’s end amasses a collection of dirt and dust in places you don’t usually pay attention to when cleaning. So now is the time to get dusting and scrubbing, airing out the futon and tossing away old things.

Preparing New Years cards (‘Nengajō’)

Once a person reaches adulthood, they usually start sending out New Years postcards, also called nengajō (年賀状). These cards are sent to relatives, friends, and people you want to show appreciation for in the past year, such as your boss or close co-workers.

With this lunar year being the year of the pig, you’ll find many nengajō with such designs.

o’toshidama and nengajō

If you have children in the family, it’s also typical to prepare o’toshidama (お年玉), envelopes of money similar to Chinese red envelopes. With Honey being a newly minted uncle, we prepared one for our baby nephew.

Many people often customize their own nengajō online. But the most typical ones are store-bought with a handwritten message like “kotoshi mo yoroshikuonegaishimasu” (今年もよろしくお願いします), which basically means ‘please look after me again this year’.

Selecting souvenirs (‘Omiyage’)

Once you’ve got your postcards mailed, it’s time to pick out o’miyage (お土産), or souvenirs to bring to the family. This culture of bringing a souvenir is not limited to New Years, but rather all occasions when you visit someone for the first time or you haven’t seen in a while.

beer gift set

If you’re not sure what makes a good souvenir, no need to panic! Around this time of year, every store has you covered. You’re likely to see gift sets of regular items (e.g. Kagome juice boxes) to prefectural snacks in any supermarket. Or you can cough up a little more cash and hit up the department store foods area.

New Years Eve

Making New Years dishes (‘O’sechi’)

Now that the family is all gathered, it’s time to get the New Years grub going. Here in Japan, people eat what’s collectively called o’sechi ryōri (お節料理). O’sechi ryōri is a variety of dishes, each with their own symbolic meaning for bringing wellness to the consumer. A lot of each dish is made so that families can spend the whole new years period munching away on them.

From the words of 5 or more native Japanese, o’sechi ryori is not very well-liked. All the dishes are cold, for easy storing and prepping, and the flavors are not always suitable to everyone’s palate. But they eat it anyway because tradition is tradition. I actually like most of the dishes. This year, Honey and I helped his mother prepare three of them.

The first is o’zōni (お雑煮), the only dish that is not cold, and that’s because it’s a soup.

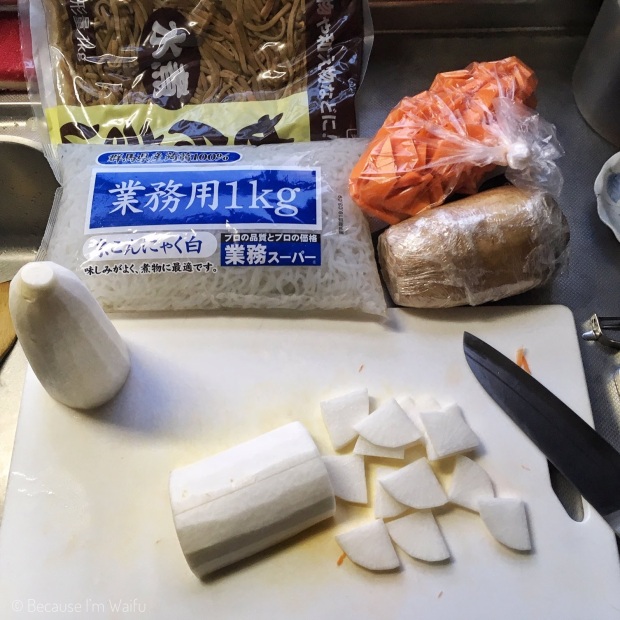

o’zōni preparation

The name itself means a simmered combination of things, thus what goes inside highly depends on the region in Japan. Our o’zōni was packed full of ingredients: daikon, carrot, rencon (lotus root), shirataki (konjac) noodles, gobo (burdock root), zenmai (a mountain plant), agedōfu and toasted mochi.

Besides all the vegetable prep-work, it’s a simple and hearty, yet healthy dish for the winter season.

Next up is namasu (なます), a dish made up of thinly-sliced daikon speckled with equally thinly-sliced with carrots. Of all the dishes, this takes the most time and patience. Afterall, you have to cut up half a daikon or more!

namasu

It’s a simple pickled dish seasoned with mainly sugar, white rice wine vinegar, and a touch of salt. For more instructions on how to make it, follow my short recipe here.

And last but not least on our prep agenda is my personal favorite, kuri kinton (栗きんとん). It’s made up of mashed sweet potatoes colored by flower seeds, which gives it its “kin” (gold), and hidden under its smooth layers are candied chestnuts, or kuri.

kuri kinton

Kuri kinton is also easy to prepare, but takes a bit of patience and arm muscle. Find my recipe for making this tasty golden dish here. If you like sweets and you like mashed potatoes, this one is for you!

Eventually there comes a time in ones life when making all the dishes gets tiring. So, many places from supermarkets to 7-Eleven actually sell prepared jubako (重箱), large squared boxes of o’sechi.

Relax and watch TV

Once the food situation is settled, it’s time to sit back and relax. And there is no better way to do that than to tune into NHK’s New Year live TV special, called Kōhaku Uta Gassen (紅白歌合戦), or “Red and White Song Battle”. It features artists whose songs were top hits the past year, with the most popular of them all giving a special performance.

69th Kōhaku Uta Gassen; top song “Lemon” by Kenshi Yonezu

As the program name suggests, the show is battle between artists split into ‘red’ and ‘white’ teams (likely mirroring the Japanese flag). At the end of the night, viewers vote for their favorite team using their TV remote.

On New Years Day, however, people can tune into the New Year Ekiden (全日本実業団対抗駅伝競走大会), a marathon competition between running teams from Japan’s corporate businesses. On the following day is the Hakone Ekiden (東京箱根間往復大学駅伝競走), a two-day collegiate marathon in the Kanto Region.

When the clock strikes 12…

While most of the U.S. welcomes the new year with a huge flash and bang of fireworks, Japan takes a more modest approach, right from the comfort of one’s dining room.

Per tradition, families either eat toshikoshi soba (年越しそば) for dinner the night of the 31st, or at midnight on the 1st. It’s typically eaten with simple toppings such as fresh negi and nori, dipped in savory soup in porcelain dishes you might confuse for regular cups (which I did).

soba at midnight!

I never expected to be eating cold noodles at 12 a.m., so I did feel a bit odd slurping them down at the stroke of midnight. But this Japanese tradition has been around for ages. Eating these buckwheat noodles signifies longevity, and a new year free of hardships.

New Years Day

Enjoy ‘O’sechi’ in a ‘Washitsu’

After enjoying that midnight meal, it’s time to hit the hay. With only hours left before sunrise, the morning after is spent setting up the o’sechi ryōri for the first official meal of the new year.

A small portion of each food is transferred to a dish, which is then placed in a specific order on special paper place-mats. Here is our setting for six people, plus an extra portion for the baby.

o’sechi ryori

At the center of the table are three dishes decorated with a plant called nanten (ナンテン), commonly referred to as the sacred bamboo. The word nanten can be written in two ways: 南天 and 難点. The latter means a “bit of difficulty”, so it’s possible these plants are used as a hopeful sign that you don’t encounter many great difficulties next year.

The meal is typically eaten at a low table inside a washitsu, or Japanese-style room with sliding doors and tatami flooring. It begins with a small toast of sake before digging in. There is no order for what foods you should eat first.

After the meal, you might enjoy some snacks and tea. In our case, we nibbled on tsujiura (辻占), sugar candies that are a New Years treat exclusive to Kanazawa, a city in central-western Japan.

tsujiura

These little candies are tough, chewy and not very tasty at all. They kind of taste like plastic. But what makes them interesting is that they contain a little fortune slip in the middle. The fortunes sound proverbial but are somewhat ambiguous, making them amusing to compare and read out loud together.

First shrine visit

If you can’t get your hands on tsujiura for your new year’s fortune, don’t worry. On New Years Day, people usually go to their local shrine for saying prayers for the coming year. At most shrines, you can get an o’mikuji (おみくじ), or fortune slip, for just ¥100. There are also special slips and trinkets for specific things as well, such as love, fortune, and academic excellence.

shrine visit

At the end of the aforementioned NHK Kōhaku music program, they pan in on a random shrine in Japan, where people are already beginning to line up for praying. Shrines are usually packed with visitors on the first couple of days, and you’ll see plenty of food vendors there too.

This is just one of many New Year traditions people take part in every year. If your new year’s resolution was to learn something new, I hope you enjoyed this post about all the interesting things Japan’s residents do to celebrate the new year.

★ Happy 2019! ★

—

-Waifu ʕ•ᴥ•ʔ